|

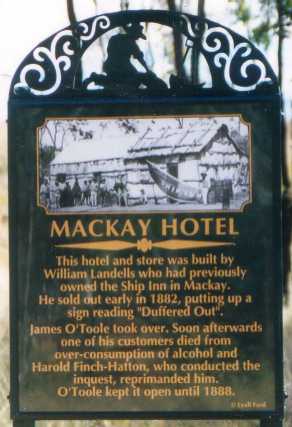

Finch-Hatton discusses the role of drink in Australia, and rails at publicans who poisoned and cheated their customers. Inquest, drunkenness, knocking down a cheque, government, drunken judge, poisoning, licensing. Finch-Hatton held an inquest on the death of a George Condon:  Historical marker

One day a man known as Ironstone George died at one of the public-houses on the field, entirely from the effects of drink. It is really infamous that no one has any power to interfere in such cases. I had seen the man hopelessly drunk, day after day, at the same public-house, and had warned the owner that I should take the first opportunity of taking away his license. Being the only resident magistrate on the field, I held an inquest on the body. In the inquiry it appeared that the publican had supplied him during a fortnight with as much liquor as he could drink, but had never given him anything to eat. A nearer approach to wilful murder it is not easy to imagine. I took the opportunity of repeating my assurance to the publican that he need never expect a license again, coupled with an expression of my unfeigned regret that the law of the land did not allow me to hang him. I was unfortunately unable to attend the first licensing board for the diggings, and the rascally local magistrates granted no less than six licenses for the Mount Britten field. These public-houses are a perfect curse all through the Bush of Australia, and no finer field was ever open to a philanthropist than a crusade against the iniquity that goes on in them. In touching upon this subject, I wish very clearly to state the ground that I take up, which is not so much reduction of drunkenness as the prevention of murder. ... Wherever a certain number of the British race are gathered together, there a certain amount of liquor will be consumed, and my own conviction is that legislation can do little or nothing to prevent drunkenness. It can, if it please, force men to get drunk in their own homes instead of in public-houses, but here its power ends. There is no truer picture of humanity than John Leech's cartoon of the British workman arriving home on Saturday night, laden with an enormous jar of liquor, to provide against the inconvenience of a Sunday Closing Act. But legislation can and ought to do a great deal towards the prevention of such monstrous crimes as are universally prevalent throughout the Bush public-houses in Australia. The most violent poisons are habitually used to adulterate the liquor sold, and to an extent which renders a very moderate consumption sufficient to destroy life. ... I have seen a strong sober man driven perfectly mad for the time being by two glasses of so-called rum, supplied to him at one of these shanties. He had not the slightest appearance of being drunk about him, but every appearance of having been poisoned, and he did not recover from the effects for a fortnight. There is not a shadow of a doubt that scores of perfectly healthy men die every year from the immediate effects of being poisoned at these infernal dens. It is a very common occurrence for a man to be found dead within a short distance of one of them. Possibly he has retained sufficient vitality to drag himself a few hundred yards on his journey, after exhausting his credit with the publican. Possibly he has actually died in the house, and been dragged a little way down the road by the publican, to avoid the unpleasantness which an inquiry into a death in his house might entail. Fear of any such unpleasantness, however, must be purely sentimental, for I never heard of a single case where any death of the kind brought serious consequences to the publican. Finch-Hatton describes the custom of "knocking down a cheque": The object of every Bush publican is to make anyone with money, who visits his house, as quickly as possible drunk, in order that he may either voluntarily hand over all he has got to the publican, and drink it out, or become so helpless as to allow himself to be robbed. A system known as "knocking down one's cheque" prevails all over the unsettled parts of Australia. That is to say, a man with a cheque, or a sum of money in his possession, hands it over to the publican, and calls for drinks for himself and his friends until the publican tells him he has drunk out his cheque. Of course he never gets a tithe of his money's worth in any shape or way--indeed, the kindest thing a publican can possibly do is to refuse him any more liquor at a very early stage of the proceedings; for cheques for enormous amounts are frequently "knocked down" in this way. A quarter of the worth of them, if honestly drunk out in Bush liquor, would inevitably kill a whole regiment. ... As if by instinct, crowds of loafers assemble at a Bush "pub." where a good cheque is going, like flies round a honey-pot, and the wildest orgies prevail. The scene is generally pretty much the same. A crowd of noisy blasphemers, enveloped in a haze of tobacco-smoke, elbowing each other to get near the counter where drinks are served. Behind this stands the barman and the landlord, the obsequious expression on the latter's face indication to the initiated that the time has not yet arrived when his conscience will allow him to declare the cheque drunk out. He is still anxious to supply everyone with everything they want. In one corner of the room lies huddled a shapeless mass, which few would suppose to be the hospitable individual at whose expense the company are drinking. An inarticulate moan bursts from the sufferer on the ground. Possibly he has been in the same position for some twenty-four hours. The landlord, who is civility itself, springs to attention at once, and hastening to him bends over him. "Beg pardon, sir--what did you please to say?" Another groan. "Certainly, sir. All right; Jim" (to the barman), "drinks for thirteen." And so it goes on. Half the men drinking at the unfortunate wretch's expense probably never saw him before, and the other half do not care if they never see him again--until he has raised another cheque. The conduct of the Queensland Government with regard to the adulteration of liquor in public-houses is perfectly scandalous. The penalties for its detection are by no means such as the gravity of the offence calls for, and are rarely enforced. The excise is most inefficient, and its duties are discharged in a way that no one acquainted with the morality of Colonial Government would credit. It is not long since the Queensland Government sent the excise round some public-houses in the neighbourhood of Brisbane. They had no difficulty in collecting a quantity of sixteen different sorts of deadly poisons, used for the adulteration of liquor. Instead of destroying them, the Government had the shameless effrontery to sell these poisons by public auction. ... A crusade against publicans is not likely to find much favour with an executive composed of men who spend half their time loafing around the drinking-bars in the town, and whose ranks generally contain one or two notorious drunkards, who are not in the least ashamed to take their seat in the House, or to be seen in the streets while in a state of intoxication. It is no uncommon thing to see a telegram in a Queensland paper to the effect that at such and such an hour "Mr. So-and-so, who was intoxicated, rose to move the adjournment of the House." Our neighbours in New South Wales and Victoria are not behind us in this respect. If anything, the Queensland Assembly is the most sober of the three. The drunkenness of the judges throughout Australia has become such a byword as to entirely deprive the time-honoured proverb ['as sober as a judge'] of any but a sarcastic meaning. It is by no means an uncommon occurrence for a magistrate or a judge to take his seat on the bench in a state of intoxication. Not long ago a most absurd scene took place at the petty sessions at a township which shall be nameless, but which is not a hundred miles from Bowen. One magistrate, as not unfrequently happens, was sitting in solitary state on the bench. His features wore that expression of ludicrous solemnity by the adoption of which a man who knows himself to be drunk endeavours to disguise the fact from his neighbours. A prisoner was brought in, charged with having removed goods to the value of 1s. 4d. from a store. Before the evidence was half finished, a terrible frown gathered on the magistrate's brow. Jamming his battered cabbage-tree hat well over his eyes, in imitation of the awful ceremony of putting on the black cap, he rose slowly up, and, pointing a shaking finger at the culprit, said: "Take'imawayand'ang'im!" "Beg pardon, your Worship," said the constable, "this is only a case of----" "Take'im-'way---and 'ang 'im!" repeated his Worship, more slowly and impressively than before. "But, your Worship," expostulated the bewildered official, "you have no power----" "No power! Just ain't I, though," shouted the now thoroughly infuriated magistrate. "'Ear what I shay? Take 'im away and 'ang 'im!" And, subsiding into his seat, he was heard to add, in a voice of maudlin pathos: "An' Lor' a mercy on his soul!" Seeing that remonstrance was useless, the constable removed the prisoner, and shortly afterwards returned. "Taken'imawayand'ung'im?" asked the magistrate, cheerfully. "Yes, your Worship." "All right. I 'shmis shcase." Some examples of publicans poisoning their customers: As long as the supervision of Bush public-houses remains in the hands of such men as these, no reform is possible. And no reform will ever come until a healthier tone as regards the subject of drunkenness pervades every class in the colony. Throughout the whole country the reputation of being mighty to mingle strong drink carries no little admiration along with it, while the fact of getting occasionally drunk entails little or no reproach. Of course, in and near the big towns the possibility of a visit from the excise makes the adulteration of liquor rather more difficult than in the Bush. Away in the back blocks it is done openly and shamelessly, and looked on, by everyone concerned, in the light of rather a good joke. A friend of mine went into a Bush "pub." near Hungerford, on the borders of New South Wales and Queensland, accompanied by three or four other men, for whom he was going to "shout." The usual invitation, "Give it a name, boys," was followed by requests on the part of his friends for various sorts of drinks. One called for rum, another for beer, and a third was just remarking that gin-and-bitters was what the doctor had ordered, when a cynical smile was observed on the landlord's face. "Hold on," he said, "it's no use going on like that. We've run out of every drop of liquor, and been drinking 'Pain-killer' for a week. So you can take that or leave it alone." On another occasion I remember hearing a man ask for a glass of gin, at a very out-of-the-way Bush shanty. He was supplied with a glass of bluish-white-looking stuff, which, after the fashion of dwellers in the Bush, he swallowed raw, intending to help himself to water afterwards. No sooner had he swallowed it than an expression of awful rage and terror came over his face. "Why, damn everything an inch high," he exclaimed, as soon as he got his breath, "that ain't gin--that's kerosene!" "Well," said the woman who had served him, "and what if it is? There's no call to make any flaming fuss. There's three gentlemen in the parlour drinking Farmer's Friend for rum, and they don't say anything." Finch-Hatton finally got a chance to crack down on the Mt. Britton publicans: On the next annual licensing day after my arrival on the diggings, I took the opportunity of refusing licenses to every single publican on the field except one.

|